What is the Internet?

The Internet -- a.k.a. the Net, the I-Net, the Information Superhighway and the

Infobahn -- is a global system of public and private computer networks. It

enables universities, governments, businesses and consumers to share files,

post notices and converse via computers, modems and phone lines.

How do all those computers talk to each other?

The Internet uses a set of

standards called TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol). They let different types of machines on different

types of networks share information. The information is transmitted through

a process called packet switching. Now, you could move a file from Computer

A to Computer B by stringing a permanent phone line between the two. But

that would be impractical and expensive. With packet-switching technology,

the file is broken up into small packets, which are individually addressed

and routed from stop to stop along the network before being re-assembled at

their final destination. It's like mailing a pack of playing cards from San

Jose to Miami -- in 52 envelopes. Other systems do roughly the same thing,

but all the computers that are technically ''on the Internet'' use TCP/IP.

Where did it come from?

The Internet -- the first packet-switching network

-- was born 25 years ago as an experimental system, funded by the U.S.

Department of Defense's Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPAnet). In the network's

earliest days, only computer scientists at a handful of research

institutions across the country were given access. As the Net grew, its

population broadened to include scientists from other disciplines.

Eventually universities came to realize the power of file-sharing, and the

Net became the communications medium for the worldwide academic community.

Only in the last several years did large numbers of consumers without

technical or academic backgrounds begin to homestead on the Net.

How big is it now?

Nobody knows for sure. And even if someone could compile

a global census, that number would be wildly out of date by the time it was

published. The annual rate of growth, depending on what's being measured

(machines, people, networks, connections) has been guesstimated at anywhere

from 55 percent to 135 percent. The Internet Society, the organization in

charge of coordinating standards for the network, says the current number

of networks is 43,000. A recent ''domain survey'' of machines with direct

Internet connections tallied 3,864,000 host computers (up from just 2.2

million in January). Each of those hosts might support 100 people or just

one lonely power-user.

The consensus guess for a total population figure is 28.9 million users.

Others contend the population may be ''only'' 13.5 million. There are

fierce arguments over how many people are truly connected to the Internet

and how many just have access to certain tools and resources.

Who uses it?

Academics collaborating on technical papers, high school kids

playing elaborate on-line games, families trading e-mail letters or baby

photos across continents and the White House press office delivering

President Clinton's latest policy speech -- those are just a few examples.

To nobody's great surprise, Internet usage correlates closely with high

education and income levels. The widely held assumption is that whites and

Asians are disproportionately over-represented on the Net. (There are no

mechanisms so far to test this hypothesis on any sample large enough to be

meaningful.) A recent MIT census of Usenet (one of the most dynamic forums

on the Net) found the average reader to be 30.7 years old. Men made up 86.5

percent of that sample.

What's out there for me?

Electronic mail (e-mail) access to millions of

your close friends, thousands of e-mail-based lists that function like

electronic magazines, more than 12,000 forums (''newsgroups'') devoted to

every topic from Spam to semiconductor design, library files stored at just

about every major university in the Western world, live conferences and

great seas of government data from weather maps and earthquake information

to photos from the Hubble telescope.

If it can be reduced to digital form (think of a long, long string zeroes

and ones) someone's probably sent it over the Net. Photographs, video

clips, music, speeches, games, computer programs and fine art reproductions

are just a few of the things other than plain text that can be sent through

the electronic pipe.

Who runs the Internet?

Nobody -- or everybody, depending on how you look at

it. Schools, governments, individuals and businesses own the hardware and

the files at their particular site. The big data-pipes (backbones) that

connect the sites are owned by a patchwork of several hundred

telecommunications companies, government agencies and universities. There

is no central governing body, although there are organizations dedicated to

making sure the Net runs smoothly. The Internet Society is the body that

sets the standards. The Virginia-based Internet Network Information Center

(InterNIC) acts as registry and clearinghouse for addresses and the like.

Is it free?

No. The Net may seem free to users on large systems because the

hidden costs are spread over so many people. But Internet access costs at

universities and businesses run in the tens or hundreds of thousands of

dollars. Individuals who initiate their own consumer accounts feel the

charges directly. They pay either a flat monthly fee or a monthly fee plus

an hourly rate for the connection.

How long will ti take me to learn?

With diligent weekend and evening study,

most people can secure a provisional license in six to eight weeks and a

permanent InterNIC Operator's Certificate in less than six months. Just

kidding. Nobody needs a license to drive the information highway. You

should be able to get around with some confidence after a few weeks. You

will never see or know the entire Net, so forget that idea. A weekend

course and a good book will do much to speed your ascent of the learning

curve. But the best resource is almost always someone who's experienced the

Net with your particular network or operating system. Before you post

questions on-line or tear your hair out calling tech-support 800 numbers,

look around for live aid. Often enlightenment is just a few steps away.

Do I have to know some special computer language?

No. You used to have to

learn basic commands in the UNIX operating system plus a lot of other

Net-specific arcana in order to get around. That's no longer true. We're

smack in the middle of a great changeover in the way people access the Net.

Today, hooking up and using a consumer account is not quite as simple as

hooking up and using a stereo, but it's rapidly moving to that level.

What is the World Wide Web (WWW)?

A seamlessly interconnected set of several

thousand sites that all share a format called hypertext markup language.

The Web, which is growing at 15 percent per month, is the hottest frontier

on the Net because it's extremely powerful, flexible and easy to use. The

beauty of the Web lies in the way documents (which can be sounds, photos or

text) are directly linked to each other. Say you're building a Web site for

screenwriters and wannabe screenwriters. In addition to your own resources,

you might want to include links in your documents that take your visitors

directly to other far-flung Web sites that feature theater or film files.

Why can't I get a video or a live concert delivered to me over the Net?

Graphics and sound files occupy huge amounts of space in comparison with

plain old text. Moving images such as live concerts and movies are even

larger. These graphic and sound files must be compressed and then sent

through wires that have a hard time accommodating huge chunks of data in a

timely manner. Then the files have to be decompressed and reassembled on

your end before you can view them. You could get a two-hour film delivered

through your modem, but it would be a very long and expensive process. This

is all going to change as connections get wider and faster. Many firms are

experimenting with Net access through cable-TV lines -- a breakthrough that

may bring connections running at speeds hundreds of times faster than

today's standard phone lines. When big pipes become common and cheap,

you'll be able to get movies on demand or live video feeds in a flash. For

now, only a small number of elite Internet users have the powerful

computers and big connections to make that sort of thing work.

Why should I do this?

That's the one question no net wizard can answer for

you. Don't do it because you're being bombarded with ''information

superhighway'' buzzwords 480 times a day. Don't do it out of some vague

fear of being left behind. It's a great big world out there, and the

Internet is just one more picture-window on it.

What does each part of an Internet address mean?

Here's the components of the Internet address aname@aserver.com:

- aname identifies a user.

- The @ symbol (pronounced "at") separates the user name from the location of the server computer.

- aserver.com identifies the location of the server computer.

Addresses use lowercase letters without any spaces. The name of a location contains at least a string and, typically, a

three-letter suffix, set apart by a dot (the period symbol is pronounced "dot"). The name of a location might require several

subparts to identify the server (a host name and zero or more subdomains), each separated by dots. For example, the address

aname@aserver.bserver.com uses a subdomain.

The three-letter suffix in the location name helps identify the kind of organization operating the server. (Some locations use a

two-letter geographical suffix.) Here are the common suffixes and organizational affiliation:

- .com (commercial)

- .edu (educational)

- .gov (government)

- .mil (military)

- .net (networking)

- .org (noncommercial)

Email addresses from outside the United States often use a two-letter suffix designating a country. Here are some examples:

- .jp (Japan)

- .uk (United Kingdom)

- .nl (The Netherlands)

- .ca (Canada)

How can I save files and images onto my hard disk?

Choose File|Save As to save a page locally (to your hard disk) in source, text, or PostScript format (UNIX only). Source

format produces a text file encoded with the HTML necessary to reproduce the formatted text or image faithfully; text format

saves text without the HTML code. Where some links, such as many FTP links, automatically download and save a file to

disk, Save As manually saves page files.

You can also save a page to disk without displaying the page onscreen. Position the mouse over a link or image, then click the

right mouse button (on Macintosh, hold down the button) to produce a pop-up menu with the items Save this Link as and

Save this Image as for saving a file. Clicking on any link with the Shift key depressed (Option key on Macintosh) also

produces a save dialog.

Saving a file to your hard disk allows you to display the page's information without any network connection. You can choose

File|Open File to display the HTML-formatted text or graphic image of any local file saved in source format (though a page's

inline images might be replaced with icons).

On Windows, you'll need to select "All Files" for GIF, JPEG, or other nontext files to show up in the Open File dialog. On

Macintosh, GIF and JPEG images are available in the Open File dialog, though for other nontext files to show up, you'll need

to hold down the Option key while selecting the Open File menu item.

The pop-up menu item View this Image lets you see an isolated image file. The pop-up menu item Copy this Image

Location copies the URL of the image file to the clipboard. Once you have the URL, you can open the image and save the

image to your hard disk in source format using File|Save As or the pop-up menu. You could also use View|Document

Source to find the URL of an inline image embedded in HTML code).

Knowing that every page has a unique URL

To understand how a single page is kept distinct in a world of electronic pages, you should recognize its URL, short for

Uniform Resource Locator. Every page has a unique URL just like every person has a unique palm print. (Arguments persist as

to which is more cryptic.)

Not only does each page have a unique URL, but also each image and frame on a page. You can access a page, an image, or

an individual frame by supplying its URL.

A URL is text used for identifying and addressing an item in a computer network. In short, a URL provides location

information and Netscape displays a URL in the location field. Most often you don't need to know a page's URL because the

location information is included as part of a highlighted link; Netscape already knows the URL when you click on highlighted

text, press an arrow button, or select a menu item. But sometimes you won't have an automatic link and instead have only the

text of the URL (perhaps from a friend or a newspaper article).

Netscape gives you the opportunity to type a URL directly into the location text field (or the URL dialog box produced by the

File|Open Location menu item. Using the URL, Netscape will bring you the specified page just as if you had clicked on an

automatic link.

Notice that the label on the location field says Location after you bring a page (or Netsite for pages from Netscape servers),

or Go to as soon as you edit the field. As a shortcut, you can omit the prefix http:// and Netscape automatically uses full URL

to complete the search.

Here are some sample URLs:

- http://home.netscape.com/index.html

- ftp://ftp.netscape.com/pub/

- news:news.announce.newusers

On Windows, the location text field offers a pull-down menu to the right of the text. The menu contains up to 10 URLs of

pages whose locations you've most recently typed into the field and viewed. Choosing a URL item from this menu brings the

page to your screen again. The URLs are retained in the menu across your Netscape sessions.

Netscape uses the URL text to find a particular item, such as a page, among all the computers connected to the Internet.

Within the URL text are components that specify the protocol, server, and pathname of an item. Notice in the URL

http://home.netscape.com/index.html that the protocol is followed by a colon (http:), the server is preceded by two slashes

(//home.netscape.com), and each segment of the pathname (only one here) is preceded by a single slash (/index.html).

The first component, the protocol, identifies a manner for interpreting computer information. Many Internet pages use HTTP

(short for HyperText Transfer Protocol). Other common protocols you might come across include file (also known as ftp,

which is short for File Transfer Protocol), news (the protocol used by Usenet news groups), and gopher (an alternative

transfer protocol).

The second component, the server, identifies the computer system that stores the information you seek (such as

home.netscape.com). Each server on the Internet has a unique address name whose text refers to the organization maintaining

the server.

The last component, the pathname, identifies the location of an item on the server. For example, a pathname usually specifies

the name of the file comprising the page (such as /welcome.html), possibly preceded by one or more directory names (folder

names) that contain the file (such as /home/welcome.html).

Some pathnames use special characters. If you are typing a URL into the location field, you'll need to enter the characters that

exactly match the URL. For example, some pathnames contain the tilde character (~) which designates a particular home

directory on a server.

Netscape Communicator Basics

Using Netscape Communicator

Netscape is a browser program designed to bring pages of the Internet

to your computer screen. With Netscape you bring one page of information

to your screen at a time and have the option of bringing up more pages

of related information. Many of these pages provide built-in connections

to other pages, called links. By clicking the left mouse button

on a link, which will usually be in a different color and underlined, you

can access another page of related information.

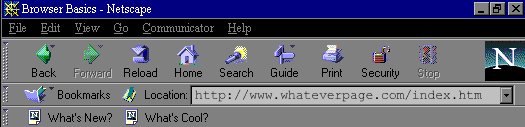

After you double-click on the Netscape icon, a screen will appear with

the following toolbar:

Features of Netscape

Bookmarks

The Bookmark menu allows you to mark pages that you want to access

easily again. Bookmarks offer a more permanent means of page retrieval

and can be used to personalize your Internet access. Using bookmarks can

be as simple or as advanced as you want. For simple bookmarks, choose Bookmarks

from the menu bar and choose Add Bookmark. Or, simply hit Ctrl-D.

Either of these methods will add the current page to your bookmark list,

giving you easy and direct access to your favorite pages.

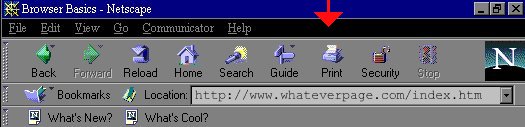

Back Button

Note the Back Button in the upper left-hand corner of the screen.

This enables you to return to the previous screen. Using this you

can always return to where you started. To return to the first screen

in Netscape, click on the Home button.

Understanding URL's

Each page on the Internet has a unique URL which is found in the Location

field on the Netscacpe screen. URL stands for Uniform Resource Locator

and is what identifies each page. It is like your telelphone number. Most

often you do not need to know a page's URL. Netscape already has the URL

available when you click on highlighted text, press an arrow button, or

select a menu item. Netscape gives you the opportunity to type in a URL

directly into the Location field. This will bring you the specified

page just as if you had clicked on an automated link.

Saving and Printing

Saving Pages

In addition to viewing pages with Netscape, you can also save a page

as a file on your computer. Choose File from the menu bar, then

choose Save As. Be warned though, this will not save the document

in the same format that you view it in. The page will be saved in HTML

format. HTML stands for Hyper Text Markup Language. This is the

language that Internet pages are written in. For an example of what HTML

looks like, hit Ctrl+U.

Printing Pages

To print the contents of the current page, choose File from

the menu bar, then choose Print. A Print dialog box appears allowing

you to select printing options and begin printing. The Netscape application

prints a page in the same width as the page appears on the screen.

Another way to print is to click on the Print button on the

menu bar.

Getting Help

Netscape has very good help pages available. Choose Help from

the menu bar, then choose Handbook. To print pages from Help,

choose File from the menu bar, then choose Print.

Internet Explorer Basics

Using Internet Explorer

Internet Explorer is a browser program designed by Microsoft (the same

company that made Windows 95) to bring pages of the Internet to your computer

screen. With Internet Explorer you bring one page of information

to your screen at a time and have the option of bringing up more pages

of related information. Many of these pages provide built-in connections

to other pages, called links. By clicking the left mouse button

on a link, which will usually be in a different color and underlined, you

can access another page of related information.

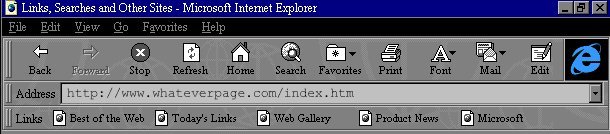

After you double-click on the Internet Explorer icon, a screen will

appear with the following toolbar:

Features of Internet Explorer

Favorites

The Favorites menu allows you to mark pages that you want to access

easily again. Favorites offer a more permanent means of page retrieval

and can be used to personalize your Internet access. Using Favorites can

be as simple or as advanced as you want. For simple Favorites, choose Favorites

from the menu bar and choose Add to Favorites. This will add the

current page to your Favorites list, giving you easy and direct access

to your favorite pages.

Understanding URL's

Each page on the Internet has a unique URL which is found in the Location

field on the Internet Explorer screen. URL stands for Uniform Resource

Locator and is what identifies each page. It is like your telelphone

number. Most often you do not need to know a page's URL. Internet Explorer

already has the URL available when you click on highlighted text, press

an arrow button, or select a menu item. Internet Explorer gives you the

opportunity to type in a URL directly into the Location field. This

will bring you the specified page just as if you had clicked on an automated

link.

Saving and Printing

Saving Pages

In addition to viewing pages with Internet Explorer, you can also save

a page as a file on your computer. Choose File from the menu bar,

then choose Save As. Be warned though, this will not save the document

in the same format that you view it in. The page will be saved in HTML

format. HTML stands for Hyper Text Markup Language. This is the

language that Internet pages are written in. For an example of what HTML

looks like, hit View and Source.

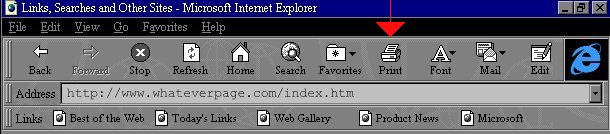

Printing Pages

To print the contents of the current page, choose File from

the menu bar, then choose Print. A Print dialog box appears allowing

you to select printing options and begin printing. The Internet Explorer

application prints a page in the same width as the page appears on the

screen.

Another way to print is to click on the Print button on the

menu bar.

Getting Help

Internet Explorer has good help pages available. Choose Help

from the menu bar, then choose Content and Index. To print pages

from Help, choose File from the menu bar, then choose Print.

|